Few recent news stories have united Americans in outrage and anger as fully as the revelations about Minnesota dentist Walt Palmer’s illegal poaching and killing of famed African lion Cecil. From Jimmy Kimmel’s heartfelt monologue to the impromptu, growing collection of stuffed animals piled in protest outside Palmer’s office, from Facebook petitions arguing for Palmer’s extradition to Zimbabwe to the voluminous quantity of negative Yelp reviews of his dental practice, critiques of Palmer’s actions have come from all corners of our culture and society. In an era when we can’t seem to agree on anything, there seems to be widespread consensus that Palmer did something deeply wrong.

That consensus is a good thing, and just might, given President Obama’s arguments for protecting African elephants on his recent trip to the continent, serve as a tipping point for international conservation efforts. Yet here in the States, we can’t critique Palmer’s actions without recognizing a complex and significant historical fact: that his actions, whatever we think of them morally, were also deeply American, part of a longstanding, multi-faceted national tradition.

In the early 19th century, as the new nation both expanded its territories and sought to establish an identity distinct from English and European ones, those efforts were reflected in the creation of new folklores. Perhaps the most popular such folklore was the group of storytellers and writers who came to be known as the Southwestern Humorists, and out of whom came the work of no less an American icon than Mark Twain. And at the heart of Southwestern Humor, as illustrated by T.B. Thorpe’s hugely popular story “The Big Bear of Arkansas,” were tales of big game hunters and their legendary exploits.

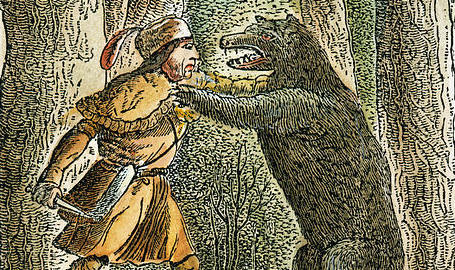

At the same time that Thorpe and his peers were creating these uniquely American hunting tales, two of the frontier’s most prominent historical figures were being turned into mythic national heroes. Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett embodied many of the frontier and nation’s mythic narratives and concepts, but none more than the role of hunting within those myths. In Timothy Flint’s bestselling 1833 fictionalized Biographical Memoir of Daniel Boone, the First Settler of Kentucky (1833), Boone famously triumphs in hand-to-hand combat with a bear; while Crockett’s mythologized connection to big game hunting is immortalized in the line, from the beloved theme song to his TV movies and show, that he “killed him a bear when he was only three.”

In 1887, New York legislator and self-styled frontiersman Theodore Roosevelt furthered the mythology of both men by founding the Boone and Crockett Club, an organized that featured big game hunting as a central component of the era’s emerging conservationism. This was the era in which virtually every railway company offered “hunting by rail” excursions, with trainloads full of Eastern travelers shooting buffalo from atop moving train cars along the length of the newly completed transcontinental railroad. Such excursions might seem unthinkably cruel and wasteful from our vantage point, but they were hugely popular—as were Roosevelt’s own famed big game hunting expeditions, which contributed immensely to his iconic image of rugged American masculinity.

These mythic narratives of big game hunting continued to inform American culture into the 20th century—from Ernest Hemingway’s larger-than-life African excursions to William Faulkner’s short story “The Bear” (1942), Disney immensely popular 1950s Davy Crockett TV show through the last few decades’ resurgence of trophy hunting as an elite pastime. To be sure, that recent trend has received more pushback and critique than in any prior moment, opposition that has been crystalized with special clarity in the aftermath of Palmer’s hunt. Yet at the same time that we make the case for an end to big game hunting as a vital element of 21st century conservation, we need to grapple with how deeply ingrained the practice is in our national mythologies and identity.

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.