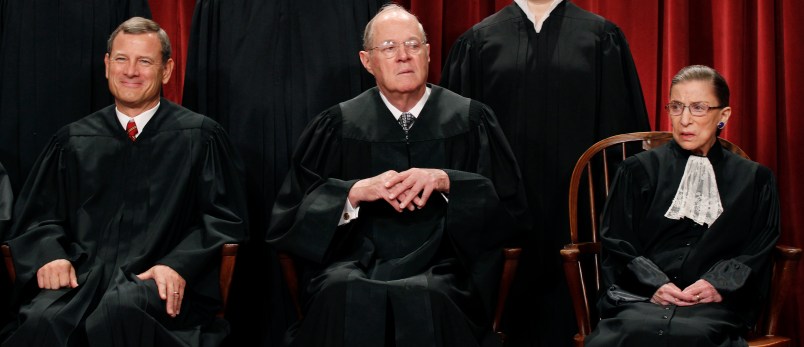

WASHINGTON — With Chief Justice John Roberts mysteriously silent, Justice Anthony Kennedy offered the most intriguing clues Wednesday about how the Supreme Court might rule in the far-reaching Obamacare case.

During oral arguments in King v. Burwell, Kennedy appeared deeply torn between the two sides, revealing himself as a potential swing vote in the lawsuit that could derail President Barack Obama’s signature domestic achievement.

Kennedy alluded to one way to uphold the Obamacare subsidies while advancing the deeply-held conservative principle of federalism, which is often translated as states rights. He argued that the text of the law could be read as prohibiting tax subsidies on the federal exchange, but warned that such an interpretation might make the law unconstitutionally coercive to states because their insurance markets would crumble under a federal exchange that lacks the authority to provide subsidies.

“From the standpoint of the dynamics of federalism, it does seem to me that there is something very powerful to the point that if your argument is accepted, the states are being told either create your own exchange, or we’ll send your insurance market into a death spiral,” Kennedy said. “We’ll have people pay mandated taxes which will not get any credit on the subsidies. The cost of insurance will be sky high, but this is not coercion. It seems to me that under your argument, perhaps you will prevail in the plain words of the statute, there’s a serious constitutional problem if we adopt your argument.”

Kennedy’s questions throughout the hourlong argument were tinged with federalism concerns. His sympathies were divided between the textual argument by the challengers and the specter of states “being coerced” into setting up exchanges under a scheme that doesn’t afford them a “rational choice.”

Conservatives noticed the Reagan-appointed jurist’s hesitations.

“I think he is wholly unpersuaded by government’s textual arguments and reluctant to grant deference, but concerned about the possibility of a federalism problem,” Jonathan Adler, a law professor and architect of the lawsuit, told TPM, saying that Kennedy could uphold the subsidies on the basis that he agrees with the plaintiffs’ view of the provision while declaring it unconstitutional. “I didn’t see how he sides with the government without doing something like that.”

Adler pointed out that such a ruling would “raise risks for other programs” erected by the federal government. Essentially, it would impose new limits on actions that Congress can take which substantially affect states.

It’s far from clear how Kennedy will rule. Progressive defenders of Obamacare aren’t getting their hopes up about winning over Kennedy, remembering that he voted (unsuccessfully) to wipe out the law entirely in 2012 and voted (successfully) against its birth control mandate in 2014.

“He asked hard questions of the plaintiffs in NFIB [the case involving the individual mandate], too. I’m loath to read too much into it,” Nick Bagley, a law professor who co-wrote a brief in defense of the subsidies, said in an email. “I doubt it’ll come to the point of issuing an explicit constitutional holding. He’s thinking mainly about avoiding the constitutional question.”

At one point, Kennedy brought up a hypothetical in which the federal government tried to withhold highway funds for states unless they reduced their speed limit to 35 miles per hour. “We wouldn’t allow that,” he said.

The idea that the Supreme Court could consider this route in the King case was floated in November by Brian Beutler of The New Republic.

The Obama administration’s lawyer, Don Verrilli, also brought up the federalism argument, but he said it compels the Court to side with the government on what the language of the law says. Kennedy’s line of questioning suggested he might rule against the government on what the language says but effectively uphold the subsidies on the basis that such language would be unconstitutional.

When Carvin pointed out that the government wasn’t making that argument, Kennedy retorted, “Sometimes we think of things the government doesn’t,” to laughs in the chamber.